Self-regulation: The first or the last defence of professionalism?

The examples of unethical journalism in Serbian media during only a month’s time are so vast, that they could fill up a book. No wonder then, that the Serbian media scene is often described as a “jungle”, “a parade of distaste and primitivism”, a field for “non-distinguishing between the truth and lies”, ”a pathology with metastases”.

In their defence, many journalists claim that the media only reflect the overall social situation. Disrespect for ethical standards, which happens on a daily basis, they say is just the tip of the iceberg built by many unresolved problems of the media system (a deficient legislative framework, dysfunctional funding, persistence of pressures on media and journalist harassment, inadequate education, etc) but also by the lack of ethical observation in the political and other social fields.

The blame-placing game goes round. While everybody accuses the journalists for polluting the public space, the journalists wonder how they can be expected to be ethical if everyone around them behaves in an unethical way. In addition, many journalists think that any effort of raising professional standards is futile in the present structure of media finances and ownership, which make the media an easy prey of hidden alliances based on interests of the political and economic elites, under deficient media legislation and ineffective regulatory bodies. A great number of journalists indeed care more about how to make ends meet with a 300 Euro average pay than to read the professional Code.

Yet, in the midst of the “media jungle”, there is one part of the profession which stubbornly insists that fighting for socially responsible and high quality journalism is worth the effort. Members of the Commission for Complaints of the Press Council – four prominent journalists, four representatives of the media industry and three respected personalities as representatives of the public - gather together once a month to decide whether specific texts produced by news agencies, daily and periodical press and news web portals violated the provisions of the

Code of Journalists of Serbia. The texts they deal with are probably not the most drastic examples of unprofessional journalism, nor those with the most damaging social consequences. Still, they carefully consider the examples brought before them by various complainants who feel directly damaged by specific media products, consider the answers given by the accused media, and make a professional judgment: the text did or did not breach concrete provisions of the professional code. The media in violation of ethical rules are obliged to publish the decision of the Press Council. This practice is two and half years old.

Starting anew

The organized fight for professional ethos is not a completely new experience for journalists in Serbia. There existed a Council of Honour in their professional organization for decades. The Council of Honour of the Association of Journalists of Serbia, however, lost credibility when it allowed instrumentalization of the profession for the goals of the nationalistic and war-oriented regime of the nineties. The establishment of the system for collective professionalization and protection of citizens of Serbia from misuse of the power of media had to start anew. Journalists decided to copy a self-regulation model of Norwegian journalists, who had a lengthy experience in this area and offered help for the establishment of the new institution.

The beginning was difficult. The new body had to overcome many problematic relations within the journalist community – a rift between two of the largest professional organizations that nourished their distinctions since 1994, adversaries between tabloid and serious press, state and private media, between national and local journalists, etc. Finally, after much difficulty, the Press Council was established in 2009 as a voluntary association of press publishers and journalists, by the agreement of two business associations - the Media Association and the Association of Independent Local Media

Local Press - and two journalist associations - the Association of Serbian Journalists (UNS) and the Independent Association of Serbian Journalists (NUNS). Funding should have been provided by the industry. Media owners, however, could not or did not want to finance the Council. After a two-year delay, the

Press Council started working in 2011, after getting a financial donation from Norway.

In a short time, the Press Council made several important achievements. By the end of 2013, the authority of the Press Council widened. From the initial 66 media outlets that were willing to publish a decision of the Council that they made a professional mistake, the number of the Press Council members increased to 78, including today 2 news agencies, 3 web portals, 13 dailies, 26 magazines and 34 local newspapers. The Council was joined by the most popular tabloid papers, which were expected to avoid membership out of fear that they would often receive Council’s warnings. The authority of the Council expanded from print media to online media as well. Most importantly, in 2013 the Press Council started accepting complaints on the work done by media outlets that did not officially embrace its authority. In these cases, the Council would issue a public warning if the violation of the Code took place, although the media in question are not obliged to publish its decision. The Council publishes a decision on its

official website.

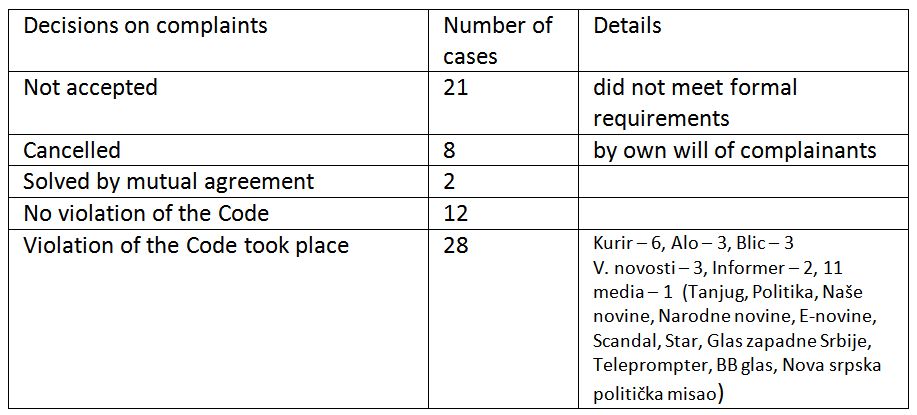

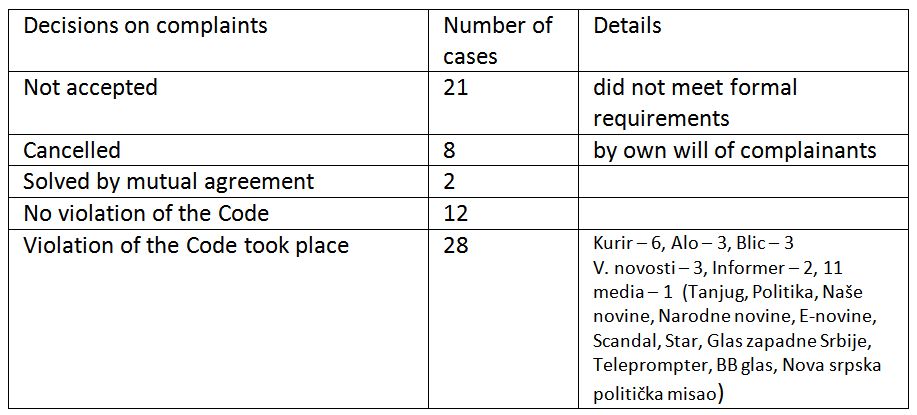

The Credibility of the Press Council increased significantly. In 2013, it received 71 complaints, twice as much as in the year before (35).1 Twenty complaints were filed by institutions and organizations (education and medical institutions, private and public business companies, NGOs, a religious organization and one ministry), five by media organizations (usually because of disrespect for copyright) and 46 by individuals. Individual complainants included some highly prominent state or party officials (Governor of the Central Bank, mayor of Belgrade, and leader of the party LSDV) who preferred to resolve their grievances by the authority of the Council than in other ways at their disposal.

The Council made 40 decisions in 2013. In 28 cases, it established that the media violated professional and ethical norms and in 12 that they did not.

In 20 out of 28 cases, the media breached several provisions of the professional code in one text. Journalists most often violated provisions on the accuracy of reporting (11 cases) proper journalist attention (nine cases) protection of privacy and non-publishing of corrections (eight cases).

According to the Press Council secretary Gordana Novaković, a very important sign of the Press Council's earned credibility is that none of its decisions was disputed by media or journalists.

The experience of the work of the Council were used for writing new provisions in the Code of Serbian Journalists concerning corruption and reporting about corruption, which were added to the existing Code in 2013.

The Council was very active in educating judiciary officials about its work and ways in which to avoid court trials related to journalists. It organized six seminars for judges and prosecutors from all major towns in Serbia in 2013. In addition, it educated local journalists and audiences in 10 towns across Serbia, which resulted in the increase of complaints on the work of local media, rarely filed in the first year of the Council's existence.

Futile or encouraging?

Industrious efforts of the first self-regulatory body have not decreased the instances of unethical media contents, nor have they changed the nature of professional blunders. Journalists continue to offer the media to their sources instead of offering sources to their audiences, speculating, discriminating, leading smear campaigns, intruding into private lives, accusing and sending to prison. Even the media outlets that voluntarily joined the Press Council fail to always observe the only sanction imposed by the Council - to publish its decision about their breach of professional norms (tabloid Kurir – four of six ones, tabloid Informer two of two, and Večernje novosti one of three) – or more importantly, continue to make the same violations of ethics because of which they had already been warned by the Council.

The Press Council remains to be the only self-regulatory body. Broadcast media do not fall into its jurisdiction. Its great weakness is

instability of funding and continuing

donor dependence.2 The Institution of a media ombudsman is unknown to domestic media community. There are no signs that the two existing public service broadcasters (RTS and RTV) plan to introduce a body that would care about the professional ethos.

The work of the Press Council appears to be a drop in the ocean. It does not have any influence on the highly unfavourable institutional setting of journalists’ work.

However, the founders of the Press Council and journalists who serve in the Council are at the same time the strongest advocates of media reforms that should radically change the economic and political environment of media functioning. They are the ones who most loudly warn that the economic position of journalists prevents them from performing the socially desirable roles, who most strongly push for restructuring of the media system, appeal to system institutions to control the use of power and insist on legal guarantees of media freedoms. They started the work that cannot by itself guarantee an increase of professional standards in the present media environment, but will be an important part of professional strength once the media come out of the current crisis situation.

The Press Secretary Council secretary Gordana Novaković is optimistic: “The development of self-regulation is a process. It needs time. I believe the real effects of our work will be seen in five-six years from now”.

Although self-regulation started late, suffers many weaknesses and gets low visibility, the sign that the strongest impetus for defending the ethical aspect of the profession comes from the profession itself proves that journalists did not give up on the core of their professional ideals. In order to find a way out of the current crisis of the profession, they have to build alliances with other actors. The first among them should be media owners. They are the ones who should provide funding for the work of the Press Council and thus demonstrate an orientation in favour of media development on strong professional grounds and accountability to the civil society.

1 Data about the work of the Press Council comes from the Annual Report of the work of the Council.

2 Skrozza, T. “Ethics in the Media: Mistakes, Self-Regulation and Raising the Standards”, ANEM Monitoring Publication IX, Anem, Belgrade, 2013, pp. 33-38.

In the midst of the “media jungle”, there is one part of the profession which stubbornly insists that fighting for socially responsible and high quality journalism is worth the effort

In the midst of the “media jungle”, there is one part of the profession which stubbornly insists that fighting for socially responsible and high quality journalism is worth the effort