For years already Serbian journalists have been describing the situation in their profession as “worse than ever”. A 13-year old democracy failed to deliver on the promise to develop free media and professional and responsible journalism.

Among both audience and journalists, majority considers journalism to be unfree, politicized and corrupted, and barely touching the topics that are of the greatest interest for the public in a critical and investigative way. Journalists see their roles as downgraded to “dictaphone holders”, a “post box” or “megaphone” of the most powerful groups in the society. The lack of self-confidence seems to be widespread across professional ranks. Majority gave up believing they could make change in the society or have influence on media autonomy.

The 2012 study based on indicators of the Council of Europe for the assessment of media freedoms showed that the Serbian media differ most from the European ideal in media economy, independence of media from political influences, labour rights of journalists and their safety. Journalists do not hold themselves responsible for these constraints to their profession, imposed from outside. However, self-critical assessments are rarely heard in their conversations about the state of the profession in regard to a whole set of factors that determine the quality of professionalism, such as professional self-organisation and self-regulation, collective protection of journalist rights based on professional solidarity, creation of a favourable mini-climate in newsrooms and stimulation of professional achievements, self-education and upgrading of personal capacities. Another missing spot in conversations about the profession are structural changes in journalism as a social institution brought about by the development of new communication technologies. Journalists in Serbia are still occupied with finding solutions for problems typical for the 20th, not the 21st century.

External constraints

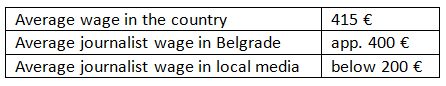

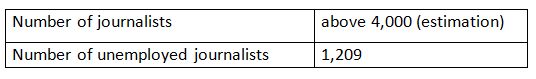

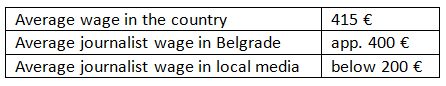

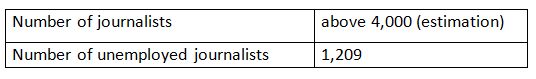

Majority of journalists points to poor economic position and weak (or no) social protection as the key factor limiting performance of their societal roles. Main negative elements of the unfavourable position of journalists have been persistent for a long time: job insecurity, small salaries, absence of social protection, low social prestige, sense of lost credibility, erosion of self-respect. Journalist work a lot, get their pays irregularly, live under high stress and pressure – they are frustrated, worried about their future, forced to take additional jobs outside journalism, and have low self-esteem.

Journalists opt for a strike only when the situation becomes absolutely unbearable, but even then their strikes are rarely effective. Reason lies in oversupplied job market. For instance, in 2011, the largest media outlet (public broadcaster RTS) received 17,000 applications for announced 100 vacancies for young professionals.

Another factor undermining a sense of public interest responsibility is a poor protection of journalists’ safety. Three journalists were murdered in the past 20 years, and only in the case of Slavko Ćuruvija, killed in 1999, one of potential perpetrators was arrested. This happened in December 2013, after an intensive work of a special commission, established in 2012 on the initiative of journalists. Four journalists were under 24-hour police protection in 2013, some of them since 2005.

Severe constraints to professional work are imposed also by constant pressures coming from outside the newsrooms. They take a wide variety of forms: cuts in subsidies or other forms of financial aid, cancellation of advertising contracts, personnel lay-offs and replacements, stop of information flow, denial of access to information of public importance, prevention of attending public events, inspection visits, competition being favoured, lawsuits and court rulings.

Inefficient self-organising and self-regulation

Though there are two large professional organisations – the Association of Journalists of Serbia (UNS) and the Independent Association of Journalists of Serbia (NUNS) – they failed to develop strong professional identity and solidarity. For years, these two organizations worked apart and had an antagonistic relationship. The split between them followed the split between “regime-controlled” journalists and “independent” ones during the 1990’s. Both associations are often criticized by non-members for neglecting professional issues in favour of political ones, promoting particular political ideologies without any concrete professional benefit.

Profession is also divided by different occupational ideologies: one cluster perceives the media as guardians of public interest, controllers of the government that should be free from personal, political or corporate agendas; others see the media as important agents of state- and nation-building. A newly emerging group of “commercial journalists” perceives the media as a form of commercial business driven by imperative of attracting as wide audience as possible in order to gain profit. They feel no responsibility for social consequences of violations of ethical rules of the profession, which they consider useless anyway.

The orientation of the profession to self-regulation is still weak. The sole self-regulatory body, the Press Council, became operational only in 2011. Although its results are encouraging, the problem of finances has not been resolved. It depends on foreign donations.

Professional culture in the newsrooms prone to political and economic pressuring

Journalists’ descriptions of professional culture in their particular newsrooms demonstrate that it rarely plays a strong positive role in strengthening the professional ethos.

As a journalist testified, “reporters are able to resist instrumentalization only if they are backed by a brave editor-in-chief who is backed by a brave director”. However, the practice to elect editorial staff on the basis of their professional authority and reputation has not taken roots. This is exceptionally the practice in media that are owned by journalists, if there is no big difference in their ownership stakes.

In publicly owned media the election of management and editor-in-chief is the competence of the national, provincial or local level public bodies. It is not rare that the change of parties in power brings the appointment of a new editor-in-chief, change of editorial line and employment of new journalists who are selected by new ruling parties. There are testimonies that the employment of new staff was carried out “by quotas for each political party in the ruling coalition.” They serve as a direct channel of political influence on media products in line with the interests of those who appointed them.

Following a similar pattern, in the majority of private media, the owner elects editors on the criteria who is best serving his interest. Protection of the owner’s interest is transmitted to the journalist conduct: a journalist of a regional daily testified that “in every journalist’s contract there is a provision saying that the journalist is obliged to work according to any instruction by the editor”; the editor-in-chief in this daily openly tells journalists “which topics and persons are not allowed to be tackled in the paper.”

Financial interest of an owner goes hand in hand with particular political affiliation. For instance, while Boris Tadić served as the President of Serbia, a Swiss-German company Ringier Axel Springer replaced editors-in-chief in two of its papers (news magazine NIN and tabloid Alo) because of negative image of the President in these papers. This company had significant revenues from state advertising in this period, reflected in the 2012 election campaign when these media gave the greatest positive publicity to President Tadić and his Democratic Party.

Drastic example of exploitation of journalists for personal interest of a media owner was the campaign that the owner of the most popular national television (TV Pink) Željko Mitrović ran in July 2013 against daily Blic because of the way this paper reported on the fatal car accident in which Mitrović’s son was involved. For days TV Pink’s news program aired very long statements of its owner, which were actually personal defamation of Blic’s editor-in-chief. This campaign, which faced no resistance from Pink’s editorial board, was stopped only when the regulatory body decided to act, with much a delay.

Nevertheless, there are positive examples when editors prevent pressures from powerful social actors onto journalists. Two widely known are the cases in which editors-in-chief of TV B92 (Veran Matić) and daily Politika (Ljiljana Smajlović) resisted pressures from the most powerful Serbian businessman Miroslav Mišković at the cost of a substantial loss of advertising revenues. However, these were exceptions that a few media can afford. By journalists’ accounts, pressures on national media most often come from the top positions of power (“cabinet of the state president”, “media advisor of the state president”, “people in charge of media in all kinds of state agencies”, “mayor of Belgrade”), from both ruling and opposition parties, as well as businessmen and PR officers of advertisers. Local media are exposed to pressures from local authorities, high party officials or their aids, directors of public companies, local businessmen, “police officers and criminal groups through their contacts in politics, business and police”.

Shining examples and less shining future

The few shining examples of journalism with integrity exist thanking to individual enthusiasm – that is journalists’ personal capacities and belief in importance of their social mission. One of them is the investigative programme of TV B92 – “Insider” – which despite humble staff (initially only an editor, investigator and producer) managed to tackle greatest social taboos in Serbia. Since 2004 it revealed murky business of powerful tycoons, corruption and nepotism in public institutions and companies, as well as various mafia networks. On many occasions public prosecution ensued after airing of the “Insider” serials. The journalistic team of the “Insider” had no special conditions of work in terms of a good pay or special technical conditions, or other forms of assistance, except for unreserved support by B92’s management and editorial board. “Insider” got popularity and respect owing to a painstaking work of journalists, who insisted on checking every piece of information, on investigating every aspect of the story and not bothering with the thoughts who they would make angry. The programme has become a symbol of investigative journalism, and the editor Brankica Stanković received many journalistic awards. At the same time, she was constantly exposed to harassment and threats, which led to her being appointed a permanent police escort since 2009, which is still in force.

The success the “Insider” has achieved and its high reputation both in the audience and among journalists, show that even in situation of high pressures Serbian journalism is capable of producing high quality results. However, the crisis of the profession will persist if the economic and social conditions for journalist work do not significantly improve.

Serbian Journalism: A Profession in Crisis

Serbian Journalism: A Profession in Crisis